Chris Schwartz is the founder and CEO of Ruffhouse Records. At various points, the label included The Fugees, Ms. Lauryn Hill, Wyclef Jean, Cypress Hill, Nas, Kriss Kross, DMX, Kool Keith, and Schoolly D. Ruffhouse sold more than 120 million records worldwide, generating over a billion dollars in sales and a multitude of Grammy Awards. Chris has been the recipient of many awards celebrating his success while earning 250 gold and platinum records.

After being a musician trying to catch a break in 1980s Philadelphia, Schwartz soared through the industry and built one of the most successful hip-hop record labels ever. He was one of the first people to possess the venerated Roland 808 drum machine. He helped Schooly D birth an entire genre, gangster rap.

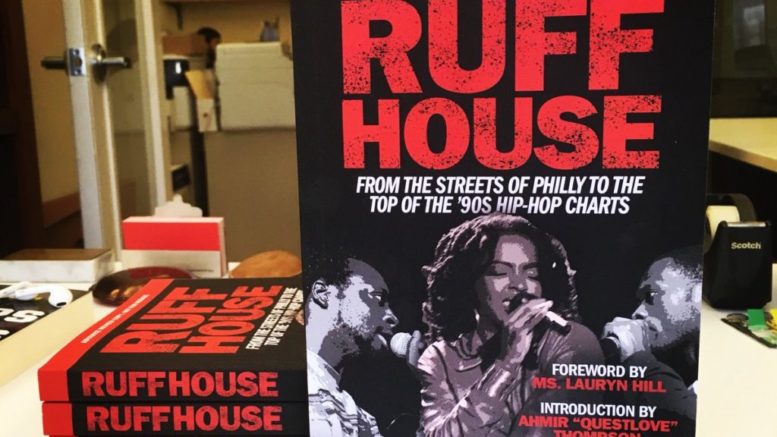

Along with his partner, Joe Nicolo he built Ruffhouse from one desk and phone to one of hip-hop’s most revered record companies. He recently wrote a book detailing all the ups and downs of his journey. The book Ruffhouse reveals an insider’s perspective of record companies, recording, touring, and the heights of hip-hop’s 1990s heyday. Ruffhouse is a great read. It offers an examination of hip-hop culture as it transformed into a worldwide commercial monolith.

When you initially started out in the record industry the executives didn’t think that white kids would buy rap music. Did this mean that they thought it would only be a genre that appealed to black people?

In the very early days, I’m talking late seventies going into 81-82, that was the audience. If you look at NYC and Chicago there were white people that listened to hip-hop records. At that point it didn’t take hold in middle America, it wasn’t a midwest thing. If you look at San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Baltimore, & Washington D.C. those listeners are just a speck compared to the potential listeners in the midwest and the more densely populated areas. So yes, were their people in large urban areas listening to hip-hop? Absolutely, but, it did not become the cultural phenomenon and cross-pollinate until later on. Scholly D was really one of the pioneering hip-hop artists who had a white audience. I saw it and to me, it was really interesting because I serviced a couple of record pools and I had this really overwhelming response from a lot of white rock clubs that wanted to book Schoolly. The DJ’s said every time they put his songs on the dance floors were packed. This was before the Beastie Boys and a lot of that stuff. In the beginning, hip-hop was a genre that wasn’t exclusive, but it was predominantly listened to by people of color in major metropolises.

So it was the Schoolly D records that made you realize that white people would start buying hip-hop?

I saw the potential, absolutely.

When was Schoolly D at his peak? He sold a lot of records and was one of the first rappers to tour Europe. What would you consider to be the height of his career?

“Gucci Time / P.S.K.-What Does It Mean?” and Saturday Night! – The Album. When we signed with Jive they told me I was only concerned with selling records to white people and that they needed to establish him at black radio. That’s a fucked up thing to tell an artist when you come right down to it. Especially if the artist is African American. Do you know what’s crazy? We were selling records. When we signed with Jive we stopped selling records. Now explain that. I think they fucked him up artistically. You know we have a new Schoolly D record coming out now. We did a song with Ice-T & Chuck D and it’s dope. It’s called “The Real Hardcore” and we use all 1980’s production elements on this record. We went back and made a record using all the stuff we did in the early days. It will be coming out early in the new year.

At what point did Schoolly start to get recognized as the creator of gangsta rap?

It all came to light when a lot of people were crediting Ice-T with his song ” 6 A.M.” as being the first actual gangster rap song. The simple reality is that “6 A.M.” is “P.S.K.” Ice-T will tell you this. He talks about it on Netflix’s Hip-Hop Evolution, he says it all the time. As a matter of fact, he even says it on the song he just did with Schoolly. I worked Eazy-E and N.W.A. for Priority. All these labels wanted to sign Schoolly. When he signed with Jive the labels came to me to market and promote their records. They all knew that Schoolly was the first guy. Schoolly was really the first independent movement in hip-hop. He had hand-drawn labels on his albums and everything. It was a totally independent operation from start to finish. I never heard records like his before that and I’ve never really heard anything like it since.

When you were running your label, Questlove was once your intern. What were his duties?

The typical stuff. He made phone calls and mailed records out.

When you first met the Fugees and they auditioned for you, it immediately struck you how Wyclef had a beatbox and a guitar, which you had never seen before. How did he use them together?

He had a drum loop on it and he was playing the acoustic guitar. He’s a very accomplished guitar player. I didn’t know he was Haitian specifically, but I knew he was from somewhere in the West Indies. I knew how important the acoustic guitar is in the Caribbean Island communities. He really knew how to play it. As he’s playing it over a drum loop I was blown away. I knew I wanted to sign them within 45 seconds. He was doing this while singing and rapping. I don’t even remember Lauryn from that audition.

At what point did you begin to realize the depth of Ms. Lauryn Hill’s artistry?

During the first album. I realized how singular her artistry was during The Score. One of the ways I knew was that people like Death Row would call my office and tell me that they were signing Lauryn Hill. I told them good luck with that. These were just people that worked there trying to intimidate us, being stupid.

At Ruffhouse Records what was the consensus opinion of the so-called “East Coast/West Coast beef” during the time it was happening?

None of us cared. Every time we put out a record it was from a global perspective.

You did have some difficulties with getting industry people to understand Kool Keith though. Could you elaborate on that?

I had trouble getting Columbia Records into the idea of doing the Dr. Octagon album. They didn’t understand it. They didn’t get it. People in the black music marketing department didn’t know how to promote it. They didn’t need to know. The same people who buy Cypress Hill would buy it. Just put it out. They couldn’t do it and then the next thing you know it’s a top 10 college record. At that point, I told them I’m doing a Kool Keith record whether you like it or not. They didn’t say anything because they saw what a mistake they’d made.

So when does your track record ever become enough?

You would think it would, right? But when you have marketing departments telling the head of a major label that they don’t know how to market a record it becomes a whole thing. They told me that if I really wanted to do the Kool Keith project that they would do it, but they weren’t going to support it. I wouldn’t do that.

Have you had to have that conversation with an artist? That you could do it but you didn’t think the parent label would support the release well enough?

Yeah, I’m not going to name any names but it caused a very ugly situation between myself and someone who’s considered very important in the business. We’re cool now, but that was a thing that definitely happened.

In the book, you said that you signed DMX and released a single but he kind of fell by the wayside. Why wasn’t there more excitement surrounding him?

It had nothing to do with that. What happened was we did a single deal with him. We didn’t put the single out for 4 months and the option lapsed. Normally Sony notified us when an option was coming up, but for some reason that didn’t happen. By the time we realized it, he had already signed with Ruff Ryders. They did such a fantastic job with him. In all honesty, I don’t know if we could have done as good. They figured out that he needed to be marketed as much as the music.

At one point you signed First Take’s Max Kellerman and released music from him and his brother. How did that come about?

Daryl Hall and John Oates brought him and his brother to us. They had originally taken them to Tommy Mottola and Tommy told them to come to us. They had a group. I found out about all the boxing stuff when we did everything. I know his brother was murdered. It’s such a shame.

You also had C.E.B. on the label, Steady B and Cool C’s group. Did you ever get bank robber vibes from them?

No. It was a total surprise. I was absolutely floored. There are professional bank robbers. People like the characters from The Town. People who know how to rob armored cars and banks. There are people who do it and can get away with it. Then you have Cool C and Steady B, who aren’t professional bank robbers but decide to rob a bank. I just don’t understand.

I remember when they had their record out. Of the groups who you discussed who didn’t make it big in your book, I thought they were the best. I liked them.

It was a great record. As a matter of fact, we had the number one rap single. Having a #1 rap single was a big deal at that time. We had all the encouragement needed to think that the album would be successful. Unfortunately, they had a manager who I don’t think was in tune with reality. Nice guy, but, he kind of made it up as he went along. I was surprised C.E.B. didn’t make it bigger.

What other acts whose lack of success surprised you?

I had two groups from Philadelphia. With them, it had nothing to do with the music. The groups just imploded. The Goats were one. They collectively sold over 400,000 records worldwide between two albums Tricks of the Shade and No Goats, No Glory. Our other acts Fugees, Cypress Hill, Kris Kross sold tens of millions of records worldwide. We got more fan mail for The Goats, from around the world, than those other acts combined. I’m talking fanmail from Eastern Bloc countries. They really struck a chord with people, but, they imploded.

We also had a rock group called Dandelion. They had a top 5 charting single and they also imploded. Drugs and alcohol man. What can you do?

I also really liked your labels group Psycho Realm. I had one of their albums and I listened to it a lot. I could really relate to a lot of what they were talking about the effects of poverty, police corruption, etc..

The only problem with them was that they were so closely identified with Cypress Hill that it became hard to distinguish them. They were kind of like Cypress, but not really. We just couldn’t get the same traction that we got with Cypress and those were kind of the expectations. Another problem they had, in all fairness to them, was that we actually left Columbia. We left right after their record came out. I feel bad about how all that went down, but it’s life. What are you going to do?

It’s amazing how much that behind the scenes stuff gets in the way of the music.

Absolutely. I had a couple of artists who had mangers who couldn’t get them to the airport. They couldn’t get this done or that done. They just couldn’t make anything happen from point a to point b. That, in turn, is really taxing on the label.

In your book, you said you partied one night with Chris Farley. Was he what we’d expect from watching him on SNL?

I partied a lot at the time. He was a cool guy, a very cool guy. Funny as shit. He was the funniest guy I’d met until I met Jim Carrey. Jim was just hysterical. He did this joke about Noah, about God talking to Noah. They had been out to sea for 32 days. God told Noah to stay away from the sheep. The way he did it though, he’s a very physical comedian. I wanted to do a record with him. The problem was that he’s so visual. The act requires the audience to see Jim.

Speaking of Saturday Night Live I thought it was dope that Cypress Hill got banned from SNL for smoking weed on TV. Did their smoking ever cause problems logistically?

Weed was never a problem. Definitely not with their behavior or professionalism. As far as logistically I don’t know how they did it. When they toured they would have road cases for bongs and stuff like that. They never let it get in the way. I have to tell you that to this day Cypress Hill has the most amazing work ethic. It definitely never hindered their artistry or output. I don’t think they really traveled with it. They had people wherever they went.

When you transferred the rights to Nas fully to Columbia did you ever consider signing AZ?

No. I was aware of him. I wasn’t quite up on everything going on with the final project, but I knew who AZ was. I believe he was already signed at that point.

You also mentioned in the book how you used to park your Rolls Royce on the sidewalk in Philadelphia. How did you begin doing that?

I really only ate at three restaurants. I tried to valet my car but they told me to park it on the sidewalk because they wanted it out front.

So they thought if people saw the Rolls that they’d think that was a place they should be eating at?

It wasn’t just a Rolls. It was a 1989 Corniche convertible. I had it restored from the frame up and it was beautiful. One of the best looking cars you’ve ever seen.

You had a pretty impressive list of cars. All high-end classics. I imagine that they were all pretty damn good looking. I didn’t see any Tahoes or Navigators mentioned.

No, I had a Navigator. I had bought a brand new Bentley, an Arnage. A Long-Wheelbase Bentley Arnage but it was the year that BMW bought Rolls-Royce and Bentley. BMW held on to Rolls-Royce, but they sold Bentley to Audi/Volkswagen. So my Arnage was really just a big BMW. BMW built the engine and everything. Every time I got in the car the top of my hair would be touching the roof. It bothered me. It also didn’t have that floaty rack and pinion I was used to. I had two Bentleys prior to this, and two Rolls Royces. I was out in L.A. and I rented a Lincoln Navigator and I loved it. Loved it. I got home and got rid of the Bentley and got the Navigator. Great car.

You were one of the first people to own a Roland 808. What made you buy it?

As you saw in the book, my best friend from childhood Jeff Coulter was a drummer. I was a guitar player. When I joined the Navy I bought a Korg monophonic synthesizer and Deagan Electravibes, an electric vibraphone that came in a suitcase. I also bought amplifiers for my guitar and things like that. I was talking to Jeff on the phone and he was telling me about the Roland. We were both Kraftwerk fans and had seen them perform. He was telling me about all these other electronic groups and all this equipment that he had. Analog sequencers and everything. I was planning on moving to L.A., but instead, I moved back to Philadelphia and formed a group with Jeff, which we named Tangent. We did strictly electronic music.

Up until the Roland 808 all factory drum machines were preprogrammed. In the ’50s if you bought one of those big Wurlitzer organs for your living room, which a lot of people did, they’d have a salsa beat and all these different preprogrammed rhythms, usually about 20. Eventually, these companies started taking these components from the organs and putting them into separate units. You could use them for instance, if you played guitar in a bar. You could use the drum patterns to accompany you for this song or that one, but, it was very limited. You couldn’t program it to play what you wanted.

We read an article that the Roland corporation was coming out with a fully programmable drum machine. This was a big deal for us. Listening to groups like Tangerine Dream, Kraftwerk, Gong, and others we came to realize that they would use clock generated components. All the drum sounds they used were basically synthetic, meaning they would create them on a synthesizer and then they would use a generated clock to create these drum patterns. We didn’t have the sophistication to do that. We weren’t at that level, these electronic bands were major acts and masters of their craft. When Roland came out with the 808, it was major for us because we could finally program our own drum patterns. We got it before it was even on the market. Through a music shop, we frequented we learned that there was an 808 in a store in D.C. that a Roland rep had left there. We arranged to buy it and it was a really big deal for us. at the time we had no inclination of what this was going to be, that this was going to become one of the most iconic drum machines in history.

A lot of people think that hip-hop started as rap music, with the DJ’s and everything like that. what really propelled the hip-hop genre was the electro-funk stuff. It was breakdancing that propelled hip-hop. Originally they didn’t make movies about rappers. All the movies were about breakdancing. What music did they use? They used Afrika Bambaataa and Soulsonic Force who sampled Kraftwerk. These were the songs they used, all the electro-funk stuff. That was the main foundational component for hip-hop. Everybody thinks hip-hop started with rapping. Yeah, it did, the shows started with emcees, but what drove it was breakdancing and those electro-funk records they sampled. You had Sugar Hill Gang and Kurtis Blow but originally much more attention was paid to the breakdancers. To Jeff and I who were devout listeners of Kraftwerk, getting this drum machine was a big thing.

Did your level of musicianship go up when you got it?

It’s funny looking back on it. The 808 isn’t the most efficient drum machine in the world. It’s great to look at, but it’s actually very tedious. Here’s the thing about it, as far as using it for live performances, you can only program it for two drumbeats at a time. It was designed to replace a drummer, live or in the studio. You could program your fills, your rolls, but it took a long time. You had to do it manually. It was kind of like an IBM keypunch system as opposed to using a Mac. If I was just messing around in the studio I’d rather use the 808 plugins. Still, if I’m going to make an actual record I’d use an actual 808. You can use digital but you can’t replicate the real thing. When you lay something down digitally you can’t really expand on it. It justs gets flatter and flatter. The key with digital is that you got to record hot for the track, once it’s there, it’s there. The more effect or boost you put on it, the thinner it gets.

You seem to be really knowledgable about the technical aspects of production and your passion for music is obvious. Why did you stop producing?

It’s funny. I’m still a musician. I play guitar every day. I’ll be honest. I started to get a very short attention span in the studio. I’m one of those people who can’t sit there and listen to the same song 175 times in the course of a session. I enjoyed it but I reached a point where I just wanted to put a gun to my head. I was never technically advanced like a lot of people. I could multi-track and a lot of that stuff. Once things got computerized, that’s where I kind of put it behind me. I could remember listening to Teddy Riley’s early records and wondering how he did those edits. I remember sitting there with Joe “The Butcher” watching him do edits by hand, sitting there splicing tape for hours. Then one of my friends bought a Pro Tools rig and I understood. Joe figured it out right away, but I looked at Pro Tools and said “huh.” At that time I didn’t even know how a computer worked. I guess I could have figured it out, but, at that point, I was more about marketing and promotion.

You’re going to be releasing some new Schoolly D music. What else do you have planned?

Right now I’m talking to distributors about a new deal. The company is called Ruff Nation. We have a multi-nation hip-hop group, No Facade. They’re composed of 11 guys. I have Kenya Vaun who’s a singer from Norristown, PA. We have a couple of other acts and we’ll be releasing a Schoolly D album.

Be the first to comment on "Chris Schwartz of Ruffhouse Released The 1rst Gangster Rap Project, & Signed The Fugees & Cypress Hill"